Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) development, and especially the pursuit of artificial superintelligence (ASI), presents unprecedented risks to international security, potentially enabling any actor who develops it first to achieve decisive strategic advantage over all others; alternatively, it may result in humanity’s extinction or permanent disempowerment.

Middle powers are particularly well-incentivized to kickstart international coordination aimed at preventing the development of ASI by any actor. In this work, we propose an international agreement which would enable a coalition of middle powers to deter dangerous AI R&D and eventually achieve a regime of international coordination in which AI R&D is restricted and thoroughly monitored in order to prevent the development of ASI.

The agreement establishes this deterrence through clearly defined AI R&D redlines tied to specific, graduated countermeasures. These measures range from export controls, through various levels of sanctions, and culminate in the recognition of self-defense rights when the most egregiously dangerous redlines are breached. Member states must commit to escalating deterrence measures in unison; this way, they may meaningfully deter dangerous AI R&D by any actor, including superpowers.

The effectiveness of this initiative critically depends on timing. Once actors are confident that they may achieve decisive strategic advantage through AI R&D, they may be willing to endure extraordinary costs and risks for a chance at permanent global dominance; earlier implementation can achieve the agreement’s goals without resorting to extreme measures.

Executive summary

Artificial intelligence (AI) development, particularly the pursuit of artificial superintelligence (ASI), presents unprecedented challenges to international security. Expert analyses suggest that the first actor to develop ASI could achieve a decisive strategic advantage—the ability to neutralize all rivals' defenses at minimal cost and maintain indefinite control over them.

Alternatively, the development of powerful AI systems may result in humanity’s extinction or permanent disempowerment, for example if a powerful AI system escapes human control. These outcomes could materialize through AI R&D activities alone, without any actor—whether a country or a renegade AI system—committing a conventional act of war until it has absolute confidence of success.

In previous work we investigated the strategies available to countries in the absence of international coordination focused on preventing dangerous AI development. We found that, in the context of a race to ASI, middle powers have little to gain and much to lose.

In this context, middle powers face catastrophic risks to their national security, with the worst case entailing the country’s complete destruction. At the same time, they lack the means to unilaterally influence superpowers to halt their attempts to develop ASI.

Middle powers may ally with a superpower, a strategy we term “Vassal’s Wager”. Even provided that their patron “wins” the race and averts catastrophic outcomes, this strategy offers no guarantee that the middle power’s sovereignty will be respected once the superpower achieves an overwhelming strategic advantage over all the actors.

We argue that it is in the interest of most middle powers to collectively deter and prevent the development of ASI by any actor, including superpowers. In this work, we lay out the design of an international agreement which would enable middle powers to achieve this goal.

This agreement focuses on establishing a coalition of middle powers that is able to collectively pressure other actors to join a regime of restricted AI R&D backed by extensive verification measures. Eventually, this coalition should be able to deter even uncooperative superpowers from persisting in pursuing AI R&D outside of this verification framework.

Key Mechanisms

Trade restrictions. The agreement imposes comprehensive export controls on AI-relevant hardware and software, and import restrictions on AI services from non-members, with precedents ranging from the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Reactive deterrence. Escalating penalties—from strengthened export controls to targeted sanctions, broad embargoes, and ultimately full economic isolation—are triggered as actors pursue more and more dangerous AI R&D outside of the verification framework.

Preemptive self-defense rights. The coalition recognizes that egregiously dangerous AI R&D constitutes an imminent threat tantamount to an armed attack, permitting members to claim self-defense rights in extreme cases.

Escalation in unison. The agreement would establish AI R&D redlines as well as countermeasures tied to each breach. These are meant to ensure that deterrence measures are triggered in a predictable manner, in unison by all participants of the agreement. This makes it clear to actors outside of the agreement which thresholds are not to be crossed, while ensuring that any retaliation by actors receiving penalties are distributed among all members of the coalition.

Though these measures represent significant departures from established customs, they are justified by AI’s unique characteristics. Unlike nuclear weapons, which permit a stable equilibrium through mutually assured destruction (MAD), AI R&D may lead to winner-take-all outcomes. Any actor who automates all the key bottlenecks in Automated AI R&D secures an unassailable advantage in AI capabilities: its lead over other actors can only grow over time, eventually culminating in a decisive strategic advantage.

Path to Adoption

We recommend that the agreement activates once signatories represent at least 20% of the world’s GDP and at least 20% of the world’s population. This threshold is high enough to exert meaningful pressure on superpowers; at the same time, it is reachable without assuming that any superpower champions the initiative in its early stages.

This threshold enables middle powers to build common knowledge of their willingness to participate in the arrangement without immediately antagonizing actors in violation of the redlines, and without paying outsized costs at a stage when the coalition commands insufficient leverage.

As the coalition grows, network effects may accelerate adoption. Trade restrictions make membership increasingly attractive while non-membership becomes increasingly costly.

Eventually, the equilibrium between competing superpowers may flip from racing to cooperation: each superpower could severely undermine the others by joining the coalition, leaving the final holdouts facing utter economic and strategic isolation from the rest of the world. If this is achieved early enough, all other relevant actors are likely to follow suit and join the verification framework.

Urgency

The agreement's effectiveness depends critically on timing. Earlier adoption may be achieved through diplomatic and economic pressure alone. As AI R&D is automated, superpowers may grow confident they can achieve decisive strategic advantage through it. If so, more extreme measures will likely become necessary.

Once superpowers believe ASI is within reach and are willing to absorb staggering temporary costs in exchange for a chance at total victory, even comprehensive economic isolation may prove insufficient and more extreme measures may be necessary to dissuade them.

The stakes—encompassing potential human extinction, permanent global dominance by a single actor, or devastating major power war—justify treating this challenge with urgency historically reserved for nuclear proliferation. We must recognize that AI R&D may demand even more comprehensive international coordination than humanity has previously achieved.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI), and in particular artificial superintelligence (ASI), is increasingly recognized as a technology with the potential to shape geopolitical trajectories. A substantial body of experts believes that AI R&D may soon deliver overwhelming strategic capabilities.[1 Alex Amadori et al.]

If ASI is built, it would likely be capable of producing a decisive strategic advantage—that is, the ability to neutralize the defenses of one’s opponents at low risk, and indefinitely maintain control over them.

As it is unclear whether the first actor to build such a system will be able to maintain control over it, ASI presents a risk of catastrophic outcomes. It is thought that ASI could lead to the permanent disempowerment of humanity or the extinction of the human species, even without any human actor deliberately setting out to produce destructive outcomes.[2 Eliezer Yudkowsky][3 Holden Karnofsky][4 Jan Kulveit, Raymond Douglas et al.]

The promise of achieving a decisive strategic advantage through AI R&D may spur an all-out AI race between the world’s superpowers. In this backdrop, middle powers find themselves in a deeply worrying predicament: if ASI is built by any actor, this will likely spell their destruction or complete loss of autonomy. Alternatively, the AI race may lead to a highly destructive major power war.[5 Alex Amadori et al.]

In this work, we design an international agreement that could enable middle powers to dissuade any actor from pursuing AI R&D which may lead to ASI, and eventually achieve a regime of coordination among all relevant powers capable of preventing the development of ASI by any actor.

This presents an unprecedented challenge: achieving full participation within an arms control agreement among all of the world’s relevant actors, without relying on any superpower to champion the agreement until it has achieved substantial participation.

2. Motivation for the proposal

As explored in our previous work[6 Alex Amadori et al.], the geopolitical prospects of continued AI progress put middle powers in a highly precarious position.

If AI systems continue improving at a rapid pace, this is likely to spur superpowers to participate in a race for developing ASI with the goal of achieving a decisive strategic advantage over all other actors. This is thought to be possible because sufficiently advanced AI may automate all key steps of AI R&D itself.

Once this happens, the speed of an actor’s AI program becomes mainly a function of its present AI systems’ proficiency at AI R&D. In other words, the actor with the best AI systems also benefits from the fastest rate of progress, and their advantage can only grow over time.

Once the lead is sufficiently large, it could be leveraged to produce strategic capabilities sufficient to neutralize all of an opponents’ defenses at low risk and maintain control over them indefinitely.[7 Situational Awareness][8 Superintelligence Strategy]

Given this dynamic, a race to ASI between superpowers would likely result in one of three outcomes:

- Takeover. An actor acquires control of a sufficiently advanced AI to grant them a decisive strategic advantage; that is, the capability to fully neutralize the defenses of all other actors and subsequently maintain control of them;

- Extinction. The development of powerful AI systems leads to the permanent disempowerment of humanity and its likely extinction.

- Major power war. All-out conflict between superpowers breaks out before AI R&D programs achieve capabilities sufficient to produce one of the other outcomes.

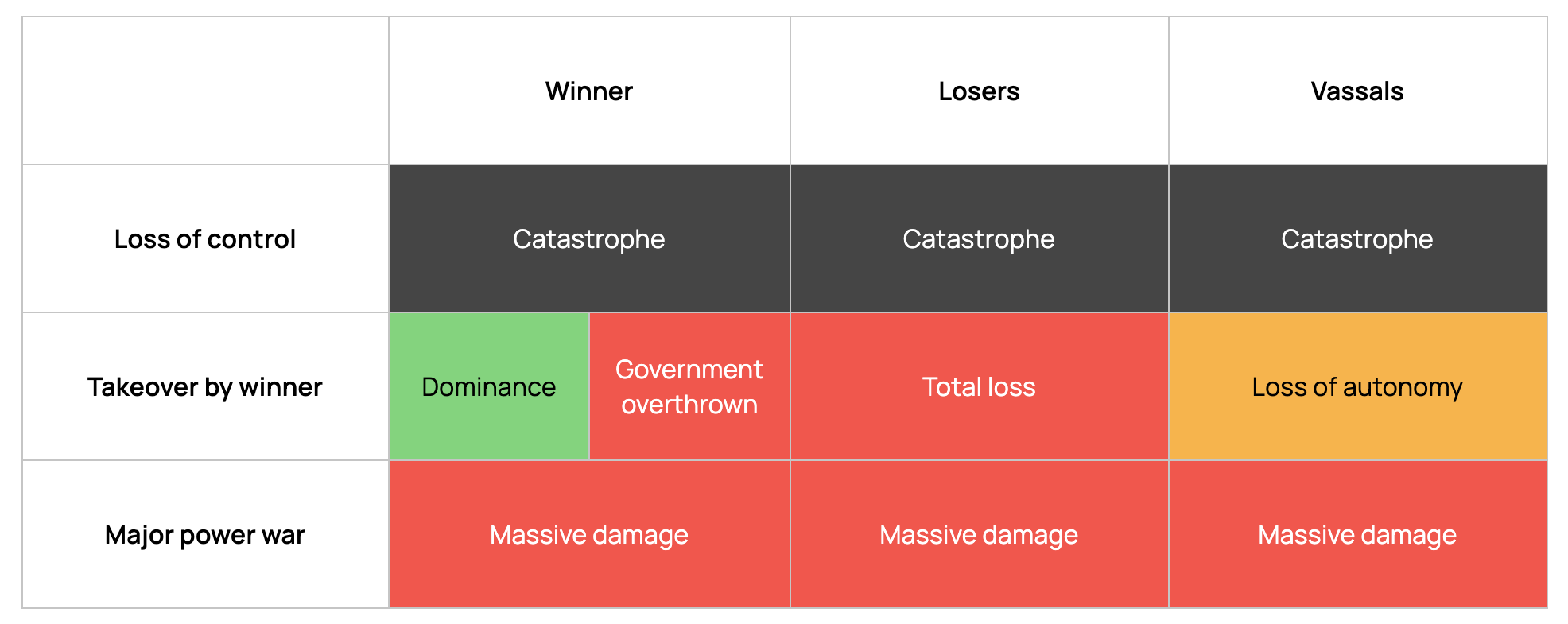

Middle powers would not be able to compete in such a race. This means that continued rapid AI progress would put middle powers in an extremely undesirable predicament. In Extinction or Major power war cases, they face utter destruction; in the Takeover case, they face complete loss of autonomy.

Desirability of outcomes by an actor’s role in an ASI race. “Winner” refers to the superpower that first achieves a decisive strategic advantage, regardless of whether this results in outcomes it considers favorable. “Losers” refers to any actors that are not aligned with the winner. “Vassals” refers to middle powers who are somewhat aligned with the winner.

Desirability of outcomes by an actor’s role in an ASI race. “Winner” refers to the superpower that first achieves a decisive strategic advantage, regardless of whether this results in outcomes it considers favorable. “Losers” refers to any actors that are not aligned with the winner. “Vassals” refers to middle powers who are somewhat aligned with the winner.Middle powers may attempt to ally themselves with their favoured superpower (a strategy we referred to as “Vassal’s Wager”). However, this strategy relies on multiple contingencies aligning favorably, with the middle power in question having little control over them: the chosen superpower must win the race, avert catastrophic risks, and subsequently respect the middle power’s sovereignty despite having overwhelming power to do otherwise.[Footnote 9]

Even if AI progress should slow down or plateau, there are several mechanisms through which weaker AI may engender geopolitical instability, with democracies and middle powers especially exposed:

- Geopolitically destabilizing military applications: weaker AI may enable novel destabilizing weapons by providing capacity of real-time control at unprecedented speed and scale. For example, it may enable massively coordinated drone swarms or missile defense systems capable of shielding against a nuclear strike.[10 Edward Geist, Andrew J. John at RAND]

- Mass unemployment and extreme power concentration: if AI leads to mass unemployment, the peoples of developed economies may lose the leverage they enjoyed from being essential to wealth creation. Political influence may become extremely concentrated in the hands of the few individuals in control of the AI systems.[11 Luke Drago, Rudolf Laine]

- Potential for micro-targeted manipulation at a massive scale: AI could produce psychologically tailored persuasion at an individual level. This could take the form of propaganda campaigns, extremely addictive AI products, impersonation and forging of evidence.[12 Alex Amadori et al.]

- Middle power vulnerability: AI progress is being driven by private companies within superpowers, particularly the US. Middle powers could lose most of their diplomatic bargaining power as most of their economy is automated by companies within superpower jurisdictions.

- Democratic vulnerability: Democracies are especially vulnerable to some of these dangers. AI may enable extreme power concentration that is antithetical to democracy, and mass manipulation could undermine public discourse.[13 Anthony Aguirre][14 Yoshua Bengio]

We contend that the majority of middle powers are strongly motivated to form a coalition aimed at pressuring other actors, especially superpowers, to join an international regime aimed at restricting AI development and preventing the development of ASI. In annex 2, we justify this claim and discuss which middle powers may be an exception.

Given this, the situation among middle powers resembles a stag hunt: a game in which the optimal action for each individual agent is to collaborate. This should make it relatively easy for middle powers to cooperate to prevent the development of ASI. In this work, we attempt to design an agreement outlining what this cooperation would entail.

3. Goal of the agreement

In this work, we present a proposal for an international agreement establishing a coalition of actors aimed at preventing the development of ASI.

The technologies targeted by this agreement could grant any actor who controls them a decisive strategic advantage. This could be achieved through sheer R&D effort, without firing a single shot.[15 Situational Awareness] Alternatively, development of these technologies could lead to the disempowerment of all human actors.

In other words, an actor with control over such technologies could effectively defeat or destroy all other countries in the world without committing, until the very final moment, any acts that would conventionally be considered an act of war.

These outcomes could materialize as long as any actor is able to develop ASI, including those outside of coalition such as the one we prescribe. This means that in order to protect their fundamental national security interests, participants would need to prevent this technology from being built anywhere in the world, not just among the signatories of the agreement.[16 Eliezer Yudkowsky, Nate Soares]

In order to prevent the development of ASI by any actor, the agreement needs to tackle the following two challenges:

- Trust: establishing mutual trust among its signatories that none of them will develop ASI;

- Pressure: Pressure actors outside of the agreement, especially those suspected of engaging in cutting edge AI R&D, to stop and eventually join the agreement.

In this work, we focus on the Pressure challenge. For the rest of this work, we assume that a framework has already been developed to address the Trust concern, and formulate our proposal as an extension of such a framework.

MIRI’s treaty proposal[17 Treaty on the Prevention of Artificial Superintelligence (draft)] (specifically articles III to X), as well as ControlAI’s “A Narrow Path”[18 Andrea Miotti et al.] (specifically phase 0 and 1) illustrate potential approaches to the Trust problem. This proposal may be merged to such an agreement, or treated as an optional module that participants can opt-in to.

For the rest of this work, whenever we refer to “the agreement”, we refer to a single international agreement that aims to solve both problems at once. This is done for the sake of simplicity, but is not a critical part of our proposal.

A particular challenge faced by our proposal is that it must be viable without assuming adoption by superpowers in its early stages. This is because, from the perspective of middle powers, superpowers are incentivized to participate in a dangerous race to ASI and cannot be relied on to spontaneously participate in such a coalition until they are under significant pressure to do so.

4. Diplomatic pressure and deterrence

Participants must urgently address the challenge of deterring actors outside of the agreement from conducting AI R&D that may lead to ASI.

In addition, they should pressure actors who haven’t yet joined the agreement to do so. ASI may be developed covertly by actors whose relevant resources are not being thoroughly monitored. [19 Paul Scharre, Megan Lamberth at CNAS] Full participation in the agreement is the only way to ensure that ASI is not built.

The rest of this section describes measures aimed at achieving these goals. We note that several elements of our deterrence framework represent significant departures from established international law customs.

We conclude this section by arguing for the necessity of these deviations, proposing that the unique characteristics of AI R&D, particularly its potential for driving winner-take-all dynamics, require unprecedented approaches to international coordination.

4.1 Restrictions on AI trade

Upon the activation of the agreement, comprehensive restrictions on AI-related commerce should be implemented between member states and non-member states.

We recommend that signatory states agree to implement the following measures:

- Export controls on high-performance computing hardware: Prohibiting the sale of AI-relevant computing hardware to non-signatories.

- Export controls on AI software:[Footnote 20] Prohibiting the transfer of AI-relevant software, such as weights or source code used for training, to non-signatories.

- Import restrictions on AI services: Prohibiting the purchase of AI-based services from non-signatories.

These restrictions align with established international law precedents. The Chemical Weapons Convention restricts the export of dual-use chemicals to States not Party [21 CWC Verification Annex Part VII, para. 31], while the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty prohibits State Parties from supplying relevant materials and equipment to Non-Nuclear-Weapon States unless the material will be subject to IAEA safeguards. [22 NPT Article III(2)]

Additionally, the US has already established a similar precedent by imposing export restrictions on advanced semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China, citing concerns around national security as justification. [23 Bureau of Industry & Security]

The trade restrictions recommended here would serve the fundamental goal of ensuring that member states do not actively support AI development outside the agreement framework, while acting as a compelling incentive for non-members to join the agreement so that they can resume AI-related trade with member states.

Additionally, import restrictions on AI services fulfill the following purposes:

- Removing some of the commercial incentive for entities in non-member states to develop cheaper AI systems by operating outside the agreement’s constraints, allowing them to undercut compliant AI developers.

- Preventing AI service providers outside the agreement framework from collecting usage data from customers within member states, as this data represents a key resource in AI development.

4.2 Reactive deterrence of AI development

We recommend that actors outside the agreement are deterred from pursuing AI R&D[Footnote 24]. This should be implemented by applying penalties toward actors that are found to pursue (or are suspected of pursuing) AI R&D outside of the agreement.

The severity of the penalties should be proportional to the scale of the actor’s R&D efforts and the sophistication of the resulting AI systems. The following examples illustrate potential penalties in order of increasing intensity:

- Strengthening of AI-related export controls and expansion of supply chain oversight measures.

- Widening of export controls to additional categories with looser relevance to AI, e.g. materials useful for chip production.

- Multiple levels of economic sanctions (including asset freezes) and targeted tariffs.

- Broader embargoes covering critical areas of commerce not necessarily relevant to AI.

- Full economic embargoes between member states and the offending actor.

This recommendation represents a significant departure from precedents set by previous international agreements. While there exists an implicit expectation that refusal to join treaties like the NPT or CWC will be met with diplomatic pressure, these agreements stop short of explicitly prescribing deterrence measures against non-member states.

Furthermore, trade restrictions between members and non-members are typically limited to each treaty's main subject matter. For instance, the CWC restricts trade in chemical weapon precursors, but does not restrict broader categories of trade under any conditions.

In the case of existing arms control treaties, there is a norm that triggering punitive measures stronger than restrictions on trade in dual-use goods requires approval by the UN Security Council (UNSC). Taking the CWC as an example again, it avoids prescribing such punitive measures through predetermined rules or through the CWC’s own processes, relying instead on referring violations to the UNSC.[25 CWC]

We also depart from this precedent, recommending that punitive measures like sanctions should not require UNSC approval. This is because, according to our analysis [26 Alex Amadori et al.], the countries that are most likely to pursue dangerous AI R&D are superpowers, which wield veto power in the UNSC. Requiring UNSC approval for measures meant to deter AI R&D would make such measures ineffective against superpowers.

As mentioned earlier, we do not assume that superpowers will join the agreement until it has gained significant traction among middle powers. In other words, we aim to design an agreement that enables a coalition of middle powers to curtail the risks arising from any actor’s AI program, including superpowers. It is therefore critical that the triggering of deterrence measures does not depend on UNSC approval.

4.3 Right to self-defense in case of egregiously dangerous AI development

We recommend that member states recognize cases of particularly dangerous AI R&D, including by actors outside the agreement, as imminent threats to the national security interests of member states, tantamount to an armed attack.

More formally, we recommend that once certain redlines are crossed, any member state may claim a right to self-defense against the offending actor. Member states should commit, at the time of joining the agreement, to recognizing that this claim is valid.

Later in the proposal, we provide guidelines for which specific acts may be considered sufficiently egregious to trigger this clause. Crucially, this instrument should be considered a last resort, to be invoked only after economic and diplomatic measures have failed to curtail gravely dangerous behavior by an offending actor. Premature use of this provision would severely damage international relations and make further cooperation efforts significantly more difficult.

This commitment does not constitute a promise to automatically engage in warfare with an offending actor, nor does it constitute a pledge from all member states to consider the crossing of such redlines as an attack upon themselves, in the fashion of NATO Article 5.

This distinction makes it possible for countries to join our proposed agreement without having to commit to waging war against actors that may currently be their allies. For example, consider the case of a middle power that maintains a military alliance with a superpower engaged in the lower tiers of dangerous AI R&D.

By avoiding the inclusion of a clause resembling NATO Article 5, we make it possible for the middle power to enter our proposed agreement without immediately breaking its alliance with the superpower. Such an alliance need not become untenable until the superpower has performed AI R&D which is considered egregiously dangerous.[Footnote 27]

This clause would represent a significant departure from established custom, in which the right to self-defense is only triggered following an armed attack, such as an unauthorized military incursion into sovereign territory or a kinetic attack. [28 UN Charter Article 51] [29 NATO Article 6] [30 CSTO Article 4] While NATO's latest Strategic Concept acknowledges that a "single or cumulative set of malicious cyber activities" could potentially constitute an armed attack, it does not explicitly recognize that the mere development of a technology could itself be considered grounds for preemptive defense. [31 NATO 2025 Strategic Concept, para. 25]

4.4 Justification of deviations from the customs of international law

We argue that the measures described in this proposal are, though drastic, necessary to fulfill the goal of preventing the development of ASI by any actor. This is because our proposal faces a challenge that is unprecedented in the realm of international coordination.

AI R&D may yield a decisive strategic advantage without an actor needing to commit any acts that would be considered, conventionally, acts of war. Automated AI R&D could allow a small lead to compound into an insurmountable one[32 Dario Amodei][33 TechCrunch][34 Leopold Aschenbrenner][35 Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh]; this, in turn, would eventually yield a decisive strategic advantage. [36 Leopold Aschenbrenner]

The same logic applies to risks such as loss of control of powerful AI systems. The point of no return where it is impossible to regain control of a rogue AI system could be reached as a result of acts that, according to previous conventions, do not constitute a justification for economic sanctions or armed self-defense. This renders existing conventions around the imposition of economic sanctions and around armed self-defense inadequate to the risks introduced by AI R&D.

The unprecedented provisions we propose, especially the recognition of preemptive self-defense rights and the mechanisms meant to empower middle power to deter superpowers from pursuing ASI, go beyond even those implemented to address the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Indeed, we argue that an agreement governing ASI development requires even more drastic measures. This is due to a critical distinction between the dynamics produced by each technology.

Nuclear weapons, when held by multiple actors, permit a form of strategic stability. As long as opposing powers develop and maintain overwhelming nuclear second-strike capabilities, a stable equilibrium may be sustained by the threat of mutually assured destruction. [37 Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara]

Even if an actor were to pour substantial resources into strengthening its nuclear capabilities, it could not develop an ability to neutralize its opponents' retaliatory capabilities before its opponents' expanded their own efforts to match.

Sufficiently automated AI R&D may upend this balance. An existing advantage in Automated AI R&D capabilities may compound and become impossible to overcome, regardless of the amount of resources invested by trailing competitors.

Absent any intervention that disrupts the leader’s AI program, such as sabotage or war, any lead can only ever grow until it produces the ability to completely neutralize the defenses of its opponents. This means that attempting to bolster one’s own AI program in order to keep up with adversaries is not an effective strategy.

In light of this possibility, economically isolating an AI superpower only in the domain of goods relevant to the development of AI may not be sufficient to deter or prevent them from developing ASI if the superpower is willing to absorb the cost.

Superpowers possess the industrial capacity and technological sophistication to maintain the full stack of required technology domestically, including the manufacturing of advanced semiconductors, the construction of energy infrastructure, the production and sourcing of vast quantities of data, and the conducting of state-of-the-art AI research.

In the gravest scenarios, as ASI comes within reach and the potential for decisive strategic advantage becomes apparent, even complete economic isolation might prove insufficient to dissuade superpowers from pursuing ASI. Superpowers may be willing and able to absorb immense temporary costs in exchange for a chance at uncontested global dominance.

5. Agreement activation threshold

We propose that the agreement enters into effect once the countries that sign it reach a threshold of at least 20% of the world’s GDP and at least 20% of the world’s population.

Individual middle powers would struggle to meaningfully pressure superpowers, and would risk being singled out in retaliation. These challenges extend to any insufficiently large coalition of middle powers.

We attempt to calibrate the activation threshold so that, at the time of the agreement's activation, the collective economic and demographic weight of member states would be comparable to that of individual superpowers.

As a result, economic isolation from member states would carry roughly equivalent impact to economic isolation from a superpower. This would also make it more difficult for superpowers to undermine an initial coalition through retaliation of economic nature.

The introduction of an activation threshold makes it possible for countries to build common knowledge of their willingness to participate once the threshold is reached, while mitigating the costs incurred by antagonizing superpowers in the initial stages of building the coalition.

Notably, this proposal has a lower activation threshold than most treaties governing weapons and dual-use resources have required historically. For example, the Chemical Weapons Convention required ratification by 65 countries before entering into force.[38 CWC]

This lower threshold reflects one of the novel challenges faced by this proposal: the constraint that it must succeed without assuming initial support from superpowers. Established arms control agreements have typically enjoyed the support of at least one superpower in their initial phases [39 CWC History] [40 Atomic Heritage Foundation], meaning that they could expect much broader initial buy-in. On the other hand, this proposed agreement must begin exerting influence without assuming widespread initial participation.

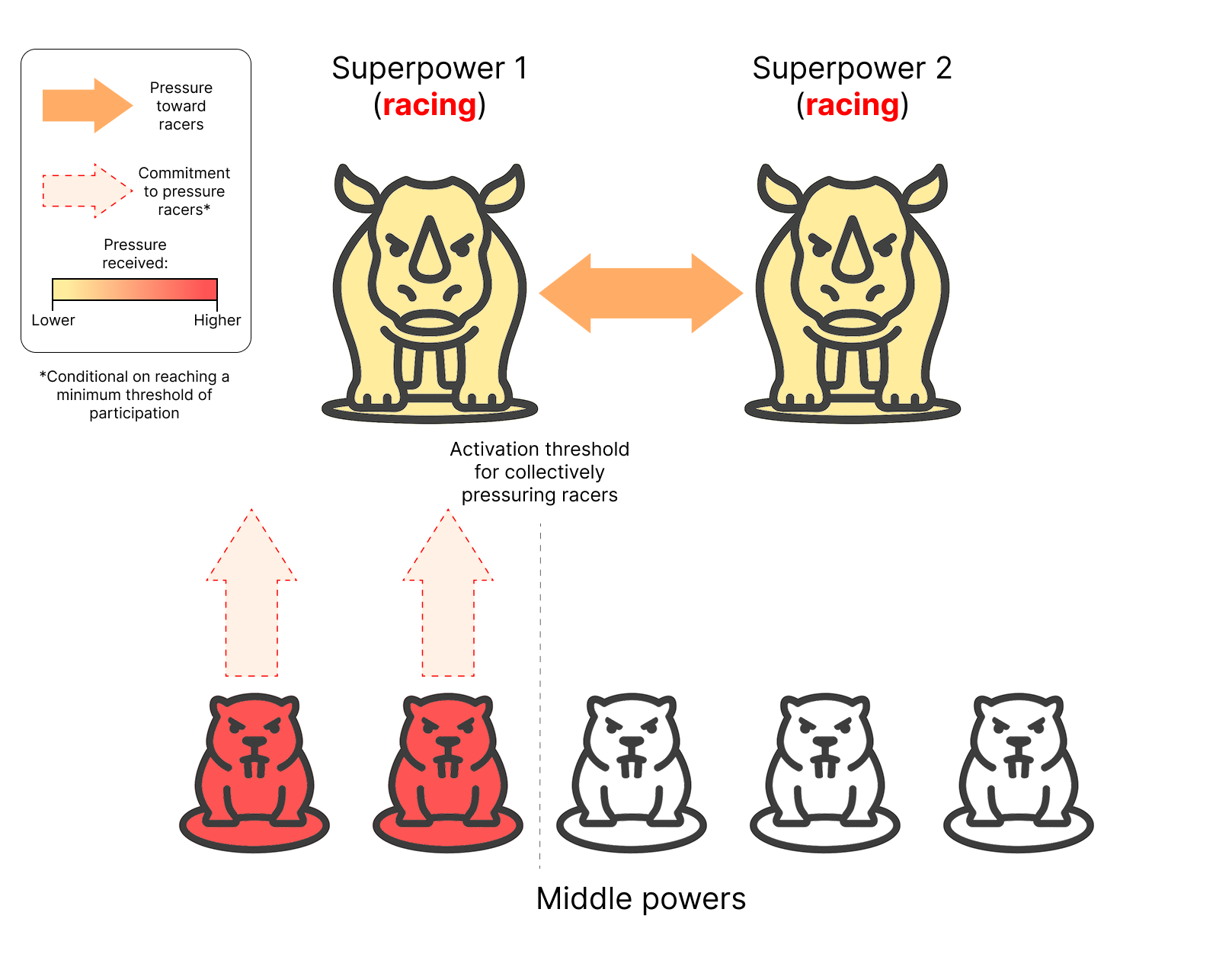

Illustration of a coalition of middle powers collectively pressuring racing superpowers to join an international agreement restricting AI R&D in order to prevent the development of ASI.

At the current level of participation, the coalition is insufficiently powerful to meaningfully pressure superpowers, and would be harshly punished in retaliation if it were to try.

However, some middle powers have already committed to participating once the agreement’s activation threshold is reached. This helps build common knowledge of the willingness of middle powers to participate in the arrangement, which is necessary in order to act in lockstep once the threshold is reached.

Illustration of a coalition of middle powers collectively pressuring racing superpowers to join an international agreement restricting AI R&D in order to prevent the development of ASI.

At the current level of participation, the coalition is insufficiently powerful to meaningfully pressure superpowers, and would be harshly punished in retaliation if it were to try.

However, some middle powers have already committed to participating once the agreement’s activation threshold is reached. This helps build common knowledge of the willingness of middle powers to participate in the arrangement, which is necessary in order to act in lockstep once the threshold is reached.

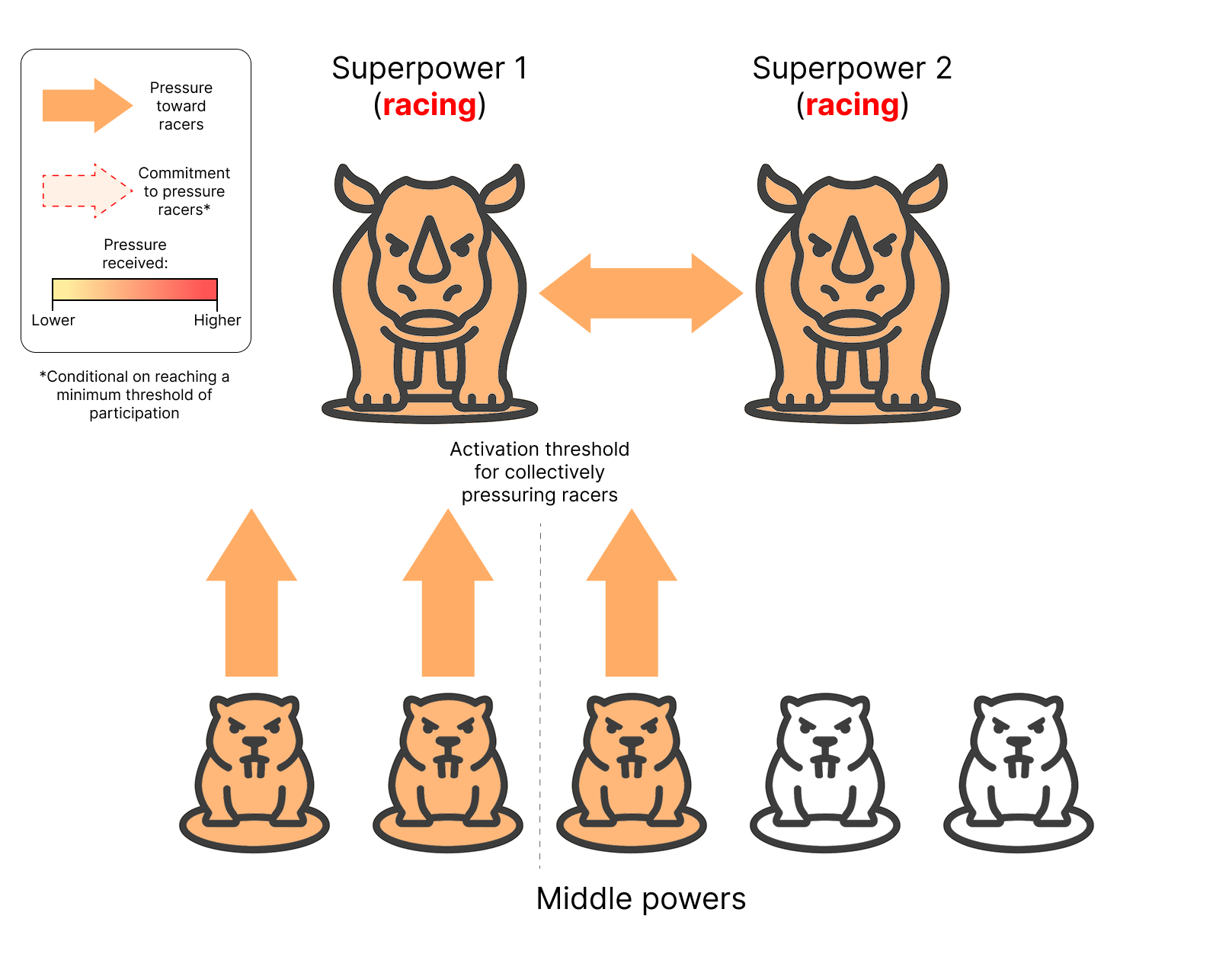

Illustration of a coalition of middle powers collectively pressuring racing superpowers to join an international agreement restricting AI R&D in order to prevent the development of ASI.

At this stage, the coalition has reached the threshold for activation, and is meaningfully pressuring actors pursuing AI R&D outside of the agreement. Any actor that is concerned about the risks of unrestricted AI development can now join the coalition without being singled out in retaliation by racing superpowers

Illustration of a coalition of middle powers collectively pressuring racing superpowers to join an international agreement restricting AI R&D in order to prevent the development of ASI.

At this stage, the coalition has reached the threshold for activation, and is meaningfully pressuring actors pursuing AI R&D outside of the agreement. Any actor that is concerned about the risks of unrestricted AI development can now join the coalition without being singled out in retaliation by racing superpowers Illustration of a coalition of middle powers collectively pressuring racing superpowers to join an international agreement restricting AI R&D in order to prevent the development of ASI.

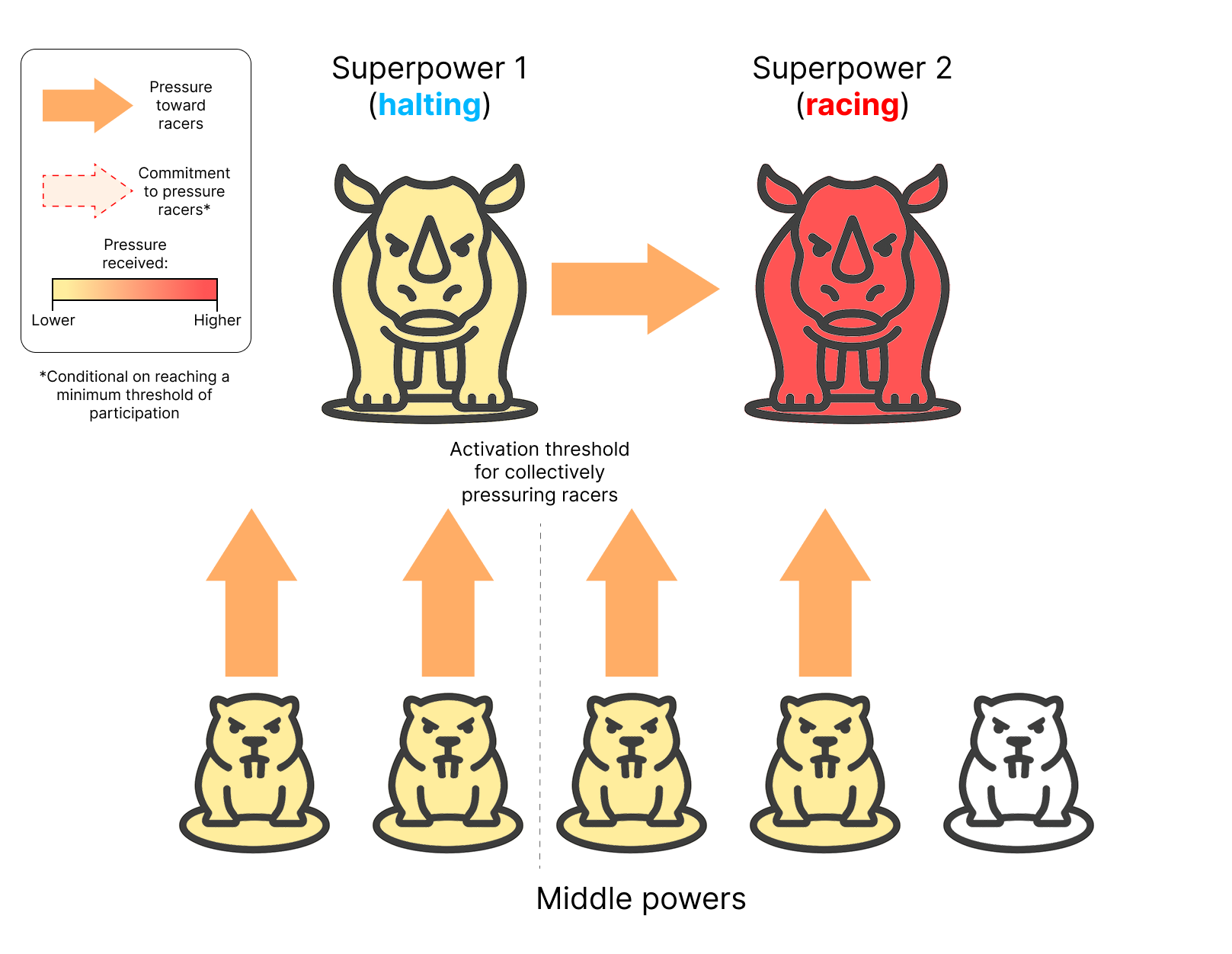

After being pressured by the coalition of middle powers, Superpower 1 has agreed to halt its attempts to develop ASI and join the coalition. Superpower 2 is now severely isolated and pressured by the majority of the world’s countries to stop pursuing AI R&D outside of the agreement framework.

Illustration of a coalition of middle powers collectively pressuring racing superpowers to join an international agreement restricting AI R&D in order to prevent the development of ASI.

After being pressured by the coalition of middle powers, Superpower 1 has agreed to halt its attempts to develop ASI and join the coalition. Superpower 2 is now severely isolated and pressured by the majority of the world’s countries to stop pursuing AI R&D outside of the agreement framework.

6. AI R&D Redlines

We propose a set of mechanisms to govern how member states collectively escalate through the ladder of deterrence measures in response to actors advancing AI R&D outside the verification framework.

This includes any actors allowing private entities within their jurisdiction to advance AI R&D in ways that are not subject to required monitoring mechanisms.

We recommend implementing multiple such mechanisms, serving complementary functions. First, redlines should be defined and agreed upon in advance, automatically triggering predetermined responses toward offending actors when crossed.

These should include both technical redlines, that provide the strictest criteria but may not address a sufficient breadth of dangers, and judicial redlines that require human judgement to evaluate, for example from expert panels or from member state representatives.

Additionally, it should be possible for a supermajority of member states to amend existing redlines and make ad-hoc decisions about escalation as circumstances evolve. This flexibility is essential given the rapid pace of AI R&D and impossibility of anticipating what future developments will look like.

As new information becomes available, such as improved understanding of AI or intelligence about the AI programs of non-member states, robust procedures should enable members to revise the escalation ladder and to address emergencies.

A periodic session (e.g. every 2 months) should be held where members can evaluate whether any redlines have been crossed and make ad-hoc decisions as needed. In addition, a minority of member states (e.g. a fifth of members plus one) should be able to trigger an impromptu session for the same purpose.

We consider it essential that escalation of deterrence mechanisms be executed by members in unison to produce adequate influence while preventing any member state from being singled out in retaliation by the offending actor. To ensure this, members should explicitly commit to executing measures in unison in the event that they are triggered.

At the same time, such commitments may also prevent premature escalation by individual members through clarifying the thresholds at which specific measures are considered justified.

Different countries may maintain different risk tolerances regarding AI R&D; additionally, some countries may harbor pre-existing grievances toward others, making them more eager to escalate punitive measures regardless of AI-related concerns. This creates a risk of escalations that are considered premature by the consensus of members.

Such premature escalation would unnecessarily sour international relations and complicate further coordination efforts. By establishing clear thresholds and establishing collective decision-making, the framework should help avoid such incidents.

6.1 Illustrative examples of redlines

We provide an illustrative set of redlines and of their corresponding deterrence measures. These are not meant to be exhaustive: we expect that the specific criteria adopted into a fully fleshed-out agreement would need to be much more extensive and operationalized in more detail. We also expect these redlines to evolve substantially as understanding of AI improves and as new information on the AI activities of non-member states becomes available.

One of the main focuses of these redlines is Automated AI R&D, which is the main hypothesized mechanism through which an actor may gain a decisive strategic advantage. In addition, they focus on other strategic capabilities like R&D of novel weapons, cyberwarfare, automation of strategic industries and automation of large parts of the economy.

In order to account for the possibility that actors conceal aspects of their AI programs in order to avoid punishment, we incorporate time-based escalation mechanisms. If an actor breaches a sufficiently grave redline and subsequently persists in their activities for a period of time, it is assumed that they may have progressed to a more dangerous stage of AI R&D even if direct evidence for this cannot be found.

Finally, these redlines attempt to address actions that increase the risks of loss-of-control of powerful AI systems. These include releasing or accidentally leaking the source code or weights for a powerful AI system, losing control of a powerful AI system, or operating a powerful AI system without adequate mechanisms in place to ensure that it doesn’t escape human control.

Technical Redlines. The triggers for these redlines are based on metrics sufficiently clear that they can be evaluated without relying on judgment by a panel of experts or member state representatives.

| Trigger | Response |

|---|---|

| Country holds computational resources above a certain threshold (including private sector). | Strengthening and widening of export controls. |

| Country possesses industrial capacity and research programs covering the full stack required for general-purpose AI development. | Sanctions and tariffs. |

| Country’s total use of compute for AI R&D exceeds a certain threshold. | Sanctions and tariffs. |

| Tasks automated by general-purpose AI comprise >= 10% of the country’s economy. | Wide trade embargo across critical industries not necessarily relevant to AI. |

| Within the country, general-purpose AI is integrated in real time command-and-control loops of weapons systems. | Wide trade embargo across critical industries not necessarily relevant to AI. |

| Tasks automated by general-purpose AI comprise >= 25% of the country’s economy. | Full trade embargo between member states and offensive nations, including both goods and services. |

| Within the country, industries relevant to military purposes are automated as a proof of concept, with no significant output. | Full trade embargo between member states and offensive nations, including both goods and services. |

| Country persists in their violation for 6 months after having crossed the “wide embargo” boundary. | Full trade embargo between member states and offensive nations, including both goods and services. |

| Actors within the country perform a large-scale cyberwarfare attack powered by general-purpose AI. | Full trade embargo between member states and offensive nations, including both goods and services. |

| Country persists in their violation for 6 months after having crossed the “full trade embargo” boundary. | Member states are recognized to possess a right to self-defense toward the offending nation. |

| Within the country, industries relevant to military purposes are automated with significantly increased outputs. | Member states are recognized to possess a right to self-defense toward the offending nation. |

| Tasks automated by general-purpose AI comprise >= 50% of the country’s economy. | Member states are recognized to possess a right to self-defense toward the offending nation. |

| Country permits a powerful AI system to be released or leaked (either intentionally, accidentally, or as a result of AI trying to escape its boundaries) | Determine the highest measure that would've been triggered by the AI system if not leaked, then trigger the measure at one level higher. |

Judicial Redlines. These redlines may deal with violations that are hard to quantify through technical metrics alone and may depend on intelligence about the activities of actors outside the agreement framework which might be difficult to obtain reliably. These criteria are necessary in order to cover a wider array of threats; it is not feasible to account for all significant risks using only technical criteria.

As a result, these criteria will need to rely on human judgement, for example by expert panels and through consensus by representatives of the member states. This will be necessary to resolve any ambiguity in the definitions and to enable varying degrees of caution in the absence of detailed information regarding AI activities of actors outside the agreement.

In this table, we use terms such as partially automated, almost fully automated, and fully automated. These terms are defined in annex 1.

| Trigger | Response |

|---|---|

| Within the country, a general-purpose AI system is developed that partially automates cyberwarfare tasks (including finding and exploiting new vulnerabilities or performing advanced social engineering), or that is considered to speed up experts performing such tasks by x3 (either serially or in terms of bandwidth). | Sanctions and tariffs. |

| Within the country, a general-purpose AI system is developed which enables non-experts to perform basic cyberwarfare tasks such as phishing attacks and simple social engineering at a large scale. | Sanctions and tariffs. |

| Actor within the country conducts an AI-powered propaganda or misinformation campaign aimed at destabilizing other countries. | Sanctions and tariffs. |

| Within the country, AI is developed that partially automates AI R&D, or that is considered to speed up an engineer or team of engineers working on AI R&D tasks by 2x. | Sanctions and tariffs. |

| Within the country, a general-purpose AI system is developed that almost fully automates cyberwarfare tasks (including finding and exploiting new vulnerabilities or performing advanced social engineering), or that is considered to enable a non-expert to perform such tasks, or that is considered to speed up experts performing such tasks by x10 (either serially or in terms of bandwidth). | Wide trade embargo across critical industries not necessarily relevant to AI. |

| Within the country, an AI system is developed that partially automates R&D on weapons of mass destruction or WMD defense systems, or that is considered to speed up experts performing such R&D work by x3. | Wide trade embargo across critical industries not necessarily relevant to AI. |

| Within the country, AI is developed that is considered to speed up an engineer or team of engineers working on AI R&D tasks by 4x. | Wide trade embargo across critical industries not necessarily relevant to AI. |

| Country is deemed capable of performing a crippling cyberwarfare attack powered by general-purpose AI. | Full trade embargo between member states and offensive nations, including both goods and services. |

| Within the country, AI is developed which mostly automates a critical bottleneck in AI R&D. | Full trade embargo between member states and offensive nations, including both goods and services. |

| Within a country, AI is developed which almost fully automates AI R&D, or that is considered to speed up an engineer or team of engineers working on AI R&D tasks by 10x. | Member states are recognized to possess a right to self-defense toward the offending nation. |

| Within a country, an AI system is developed that almost fully automates R&D on weapons of mass destruction or WMD defense systems, or that is considered to speed up experts performing such R&D work by x10. | Member states are recognized to possess a right to self-defense toward the offending nation. |

| Country permits a powerful AI system to escape its control, or operates a powerful AI system without adequate mechanisms in place to maintain control of it or shut it down if it becomes uncooperative. | Member states are recognized to possess a right to self-defense toward the offending nation. |

6.2 Counteracting concealed AI R&D efforts

Once redlines are established, actors outside the agreement may begin concealing information about their AI R&D and usage of AI. In this case, it will probably be impossible to distinguish with certainty when an actor has crossed any of the specified thresholds based solely on public information.

To address this problem, we recommend the following measures.

Intelligence sharing agreement. Member states should commit to sharing intelligence relevant to suspected violations, both by member states and non-members, through secure channels.

Decisions about escalation of deterrence measures should be informed by intelligence collected through these channels. In particular, this information should be shared with any member state delegates and experts participating in collective decision-making processes about deterrence.

Escalation on observed use of compute. It may be determined by the coalition that, given their current intelligence gathering capabilities, they are unable to discern if a non-member state is committing a violation.

In these cases, we recommend that deterrence measures are escalated based on observed compute usage. AI R&D requires use of a large amount of highly concentrated computational resources, which may be detectable by methods such as supply chain monitoring or thermal satellite imaging.

We recommend that member states adopt a risk-averse posture with respect to compute usage patterns. Member states may assume that the most concerning plausible redline, given the actor’s observed compute usage, has been crossed and escalate accordingly.

7. Cost-sharing and positive incentives

Some actors occupy critical positions in AI supply chains and would have an outsized impact if they implemented trade restrictions on AI-relevant hardware[41 Alex Amadori et al.] as indicated by this agreement. These include:

- The Netherlands, sole producer of EUV lithography machines;

- South Korea, major manufacturer of memory chips;

- Taiwan, the world’s leading manufacturer of cutting edge logic chips.

However, just as these actors could significantly delay AI progress by implementing trade restrictions, they may face severe consequences from doing so; this ranges from substantial economic losses to severe geopolitical vulnerability in Taiwan’s case.

In such cases, special arrangements could be negotiated. When an actor accepts outsized costs by implementing the agreement’s prescribed measures, the rest of the coalition could pool resources and offer to offset these costs. For example, the coalition could reimburse an actor for some of the anticipated economic losses.

Some proposed international AI coordination frameworks include proposals to centralize AI R&D efforts to a single research institution working under comprehensive multilateral oversight.[42 Andrea Miotti et al.] This research would be subject to strict constraints around safety, and would only perform experiments when there is broad scientific and multilateral consensus that it would be safe.

If such a research institution was created, it could establish a compelling incentive for actors to join the arrangement. This comes from the fact that any methods developed by the institution would need to remain secret, as they could otherwise be used by actors to unilaterally boost their AI capabilities to unsafe levels.[Footnote 43]

Instead of publishing the methods it discovers, the institution could provide API access to the AI capabilities it develops. This suggests a natural incentive mechanism: any actor joining the agreement would gain usage rights to the API.

8. A path to widespread adoption

We describe how our proposed agreement could achieve widespread adoption.

8.1 Initial participation by middle powers

Middle powers are well-incentivized to prevent the development of ASI. However, at the individual level, they would struggle to pressure superpowers to stop working toward ASI. If they implemented the measures we describe at the individual level, they would severely isolate themselves from an economic standpoint and invite targeted retaliation.

However, if they formed a sufficiently powerful coalition, they may meaningfully affect the strategic balance for superpowers, while mitigating the problem of economic isolation and diffusing any retaliation.

The initial activation threshold we propose ensures that the first countries to join the agreement need not pay the costs of participation in the case that the agreement does not gain traction. This makes it possible to overcome early inertia, and reach the stage where participation is advantageous to middle powers.

Countries that were not sufficiently concerned about the risks of AI development to be pioneers in terms of international coordination may join later, when participation is less costly or even positively incentivized due to our proposed restrictions on AI trade.

This means that the agreement may be successfully kickstarted by only a handful of highly motivated first movers, after which it can gain widespread adoption more easily.

8.2 Superpower buy-in

As more and more middle powers enter into the agreement, at some point, the equilibrium between superpowers could flip from racing to cooperation. For example, consider a scenario in which most middle powers in the world have already joined such a coalition, and two holdout superpowers are engaged in an AI race.

At this point, any of the superpowers would be able to severely and immediately undermine the others by joining the coalition. After doing this, the last racing superpowers would suffer utter economic and strategic isolation from most of the rest of the world, depending on which redlines it had crossed by then. It is likely that all relevant actors would join the agreement soon after, solidifying an equilibrium of cooperation.

For this transition to occur, it is critical that deterrence mechanisms are sufficient to discourage superpowers from racing. To accomplish this, deterrence mechanisms should scale proportionally to the ASI ambitions of racing actors. We believe that a deterrence framework such as we propose would serve this purpose, in all but the most extreme cases.

However, we acknowledge scenarios in which even such comprehensive isolation is not sufficient to dissuade the final holdout superpower from continuing its AI R&D program outside the agreement. In particular, if the race has progressed far enough, superpowers might be highly confident in their ability to quickly reach overwhelming AI capabilities.

In this case, they may be willing to take severe economic isolation, sabotage, and potential military confrontation as a temporary price for a chance at total victory. In such scenarios, it may prove impossible to stop these actors’ AI programs, short of an attack directly aimed at disabling their AI program.

We cannot make a confident prediction that an international agreement like the one we propose would eventually achieve buy-in from superpowers. However, we consider this likely as long as widespread participation in the agreement is realized early enough, before any actor is confident that it will achieve a decisive strategic advantage through AI R&D.

9. Conclusion

Preventing the development of ASI by any actor poses multiple unprecedented challenges in international coordination. Any actor who first builds it may achieve a decisive strategic advantage through R&D activities alone, without committing any conventional acts of war; this includes any sufficiently powerful AI systems if it escapes human control.

At the same time, middle powers cannot trust superpowers to champion the required coordination efforts. In order to enable middle powers to achieve this goal, we propose an international agreement dedicated to forming a coalition of actors that pressure others to join a verification framework on the prevention of ASI development, and deter AI R&D outside of this framework.

In order to prevent ASI from being developed anywhere in the world, the proposed agreement must achieve sufficient initial participation to exert meaningful deterrence on actors who may be pursuing AI R&D in an unrestricted manner, including on superpowers if necessary, and without assuming initial buy-in by any superpower.

The activation threshold we propose—at least 20% of world GDP and at least 20% world population—attempts to balance these competing demands. Once sufficient participation is achieved, network effects may accelerate adoption: as the coalition grows, costs of remaining outside increase while benefits of membership rise, potentially triggering a cascade of accessions.

The effectiveness of such an arrangement depends critically on timing. As automated AI R&D becomes increasingly feasible, the window for establishing coordination narrows. Earlier, adoption may be achieved through softer diplomatic pressure. Later, when superpowers are more confident they may achieve a decisive strategic advantage through AI R&D, more extreme measures may be necessary to persuade them to join the verification framework.

The stakes—potentially encompassing human extinction, permanent global dominance by a single actor, or devastating major power war—justify treating this challenge with urgency historically reserved for nuclear proliferation[44 Center for AI Safety], while recognizing that AI R&D may demand even more comprehensive international coordination than humanity has previously achieved.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Oliver Sourbut and Mitchell Howe for their thoughtful feedback and insightful suggestions.

Annex 1: Definitions of AI and automation levels

Throughout this paper, we refer to concepts such as “AI” and “partial automation”, which require further clarification. In this annex, we propose definitions of AI and of task automation that may be used in the context of an international agreement.

AI. We propose that a software system is classified as an AI system if it is classified as either a:

- Found system: A software system which is produced by large amounts of computation, such as mathematical optimization algorithms or a large amount of work performed by another AI system;

- Scaffolding software: Any software system that relies on an AI system as one of its components.

This definition aims to cover large language models (LLMs) and other neural networks through the definition of “found systems”. It also aims to cover software that is meant to enhance the capabilities of “found systems”, such as agent frameworks or memory-management systems, through the definition of “scaffolding software”.

Task automation. We propose a criterion to determine the degree to which a task has been automated. This enables the formulation of restrictions which apply before full automation of a task is achieved.

| Level of Automation | Description |

|---|---|

| Not automated, the software system is being used as a tool. | A software system generates suggestions for actions which are directly used less than ~25% of the time. A human operator uses the suggestions as starting points that are then heavily edited; for example, using them as rough initial drafts, for creative inspiration, or to offload some routine work. |

| Ambiguous range, decided on a case by case basis. | A software system generates suggestions for actions which are directly put into use about 50% of the time, but are otherwise rejected or heavily edited by a human operator. |

| Partially automated | A task can be performed by a software system under human supervision, though the human needs to reject a large percentage of attempts (~25%) or manually refine or edit the outputs of the software system before they are used. |

| Almost fully automated | A task can be performed by a software system under human supervision, where the human needs to reject a small percentage of attempts (~5%) and seldom or never needs to manually refine the outputs of the software system before they are used. |

| Fully automated | No human intervention is needed; the system's outputs are used directly. Otherwise, human approval is nominally required, but the system’s suggestions are nearly always accepted. |

Annex 2: The costs and benefits of caution

While limitations meant to curtail the development of ASI and other dangerous AI capabilities would avert the worst outcomes, it will also necessarily result in delaying the development of many benign applications of AI that would provide large economic and scientific gains.

Under the current paradigm, the promise is that AI capabilities relevant to benign applications will emerge spontaneously as general-purpose AI systems become more powerful. We currently lack the technical capacity to selectively add or remove capabilities from AI systems, or to produce powerful AI that doesn’t have certain undesired capabilities in the first place. This includes dangerous capabilities. [45 Jason Wei et al.]

Until such capacity is developed, any restrictions aimed at preventing the emergence of dangerous AI would necessarily hinder or even prevent most frontier research on general-purpose AI.

Many experts expect that AI will plateau before reaching such dangerous capabilities. [46 Alex Amadori et al.] Given this, some actors may prefer a laissez-faire approach to AI development, allowing countries or private entities to drive progress in a largely unrestricted fashion. The question we ask is: what type of actor favors such an approach?

We expect countries to be highly risk-averse in matters of national security. Threats to a nation’s existence, the functioning of its institutions, and the safety of its citizens typically outweigh even the prospect of spectacular economic or scientific gains.

Put differently, for a country to favor a laissez-faire approach, it would need to be confident that unrestricted competition in AI R&D would not have a grossly destabilizing effect on either international relations or its own security.

To put this in more concrete terms, an actor would need to be confident that AI progress will plateau before reaching destabilizing capabilities such as:

- Being able to perform most AI R&D work. Automated AI R&D is the most commonly hypothesized mechanism for how ASI could be developed in a short timeframe;.[47 Barry Pavel et al. at RAND]

- Automation of R&D of novel weapons. This may deliver disruptive military capabilities;[48 Situational Awareness] [49 AGI's Five Hard National Security Problems][50 Superintelligence Strategy]

- Enabling the deployment of new weapon systems by providing the capacity for real-time control of at a scale otherwise unobtainable. Even AI systems significantly weaker than ASI may enable large-scale operation of weapon systems and weapon-defense systems, including ones that may undermine the balance of nuclear deterrence. [51 Alex Amadori et al.][52 Situational Awareness]

Note that even if AI progress ultimately cannot deliver these capabilities, this may not be evident to AI superpowers until too late. Specifically, they may not be evident until after geopolitical tensions have already escalated—potentially to the point of war.

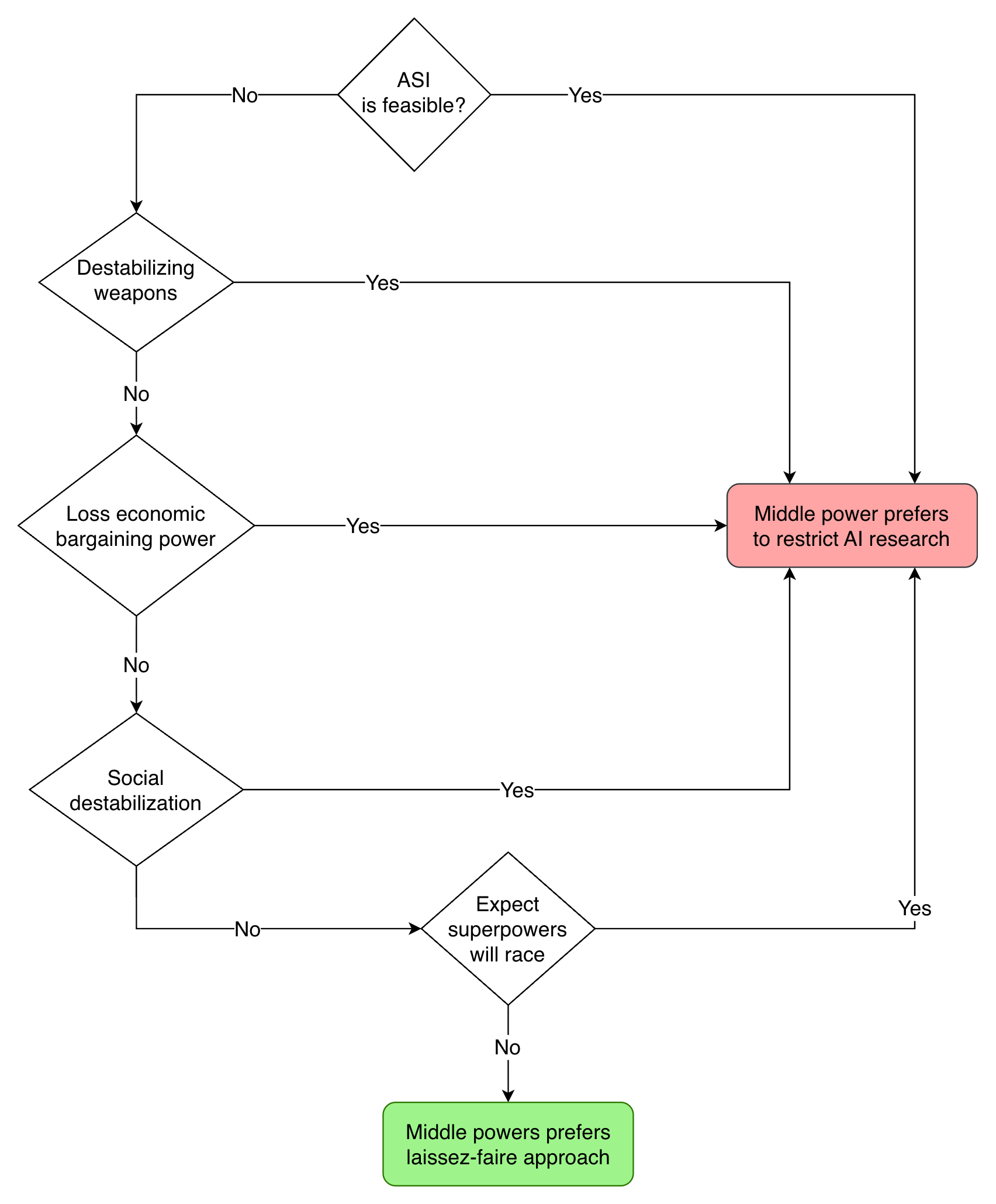

Flowchart illustrating how a middle power’s beliefs inform its preference over whether AI R&D should be restricted.

In order to prefer a laissez-faire approach, a state actor should believe that: (1) ASI is not feasible in the short-term; (2) Weaker AI will not enable disruptive weapons, such as missile defense systems that may threaten the MAD logic; (3) that the middle power will not lose diplomatic and economic bargaining power as a result of superpowers automating a large portion of their economy; (4) that AI will not be socially destabilizing for the middle power, for example by undermining democratic institutions.

Finally, even if a superpower is fully convinced that ASI and disruptive AI-enabled weapons are not feasible, that may not stop superpowers from believing otherwise. Superpowers may still attempt to gain such capabilities, and tensions may escalate as a result.

Flowchart illustrating how a middle power’s beliefs inform its preference over whether AI R&D should be restricted.

In order to prefer a laissez-faire approach, a state actor should believe that: (1) ASI is not feasible in the short-term; (2) Weaker AI will not enable disruptive weapons, such as missile defense systems that may threaten the MAD logic; (3) that the middle power will not lose diplomatic and economic bargaining power as a result of superpowers automating a large portion of their economy; (4) that AI will not be socially destabilizing for the middle power, for example by undermining democratic institutions.

Finally, even if a superpower is fully convinced that ASI and disruptive AI-enabled weapons are not feasible, that may not stop superpowers from believing otherwise. Superpowers may still attempt to gain such capabilities, and tensions may escalate as a result.This means that even a confidently bearish technical thesis may not suffice to make an actor favor a laissez-faire approach at a global scale; it is also necessary that such a thesis be evident to superpowers.[53 Zachary Burdette, Hiwot Demelash at RAND]

Finally, we must consider the range of societal, economic, and regulatory challenges that AI may present, such as concentration of power[54 Luke Drago, Rudolf Laine] and the potential for large-scale manipulation by AI systems.[55 Matthew Burtell, Thomas Woodside][56 Anthony Aguirre]

In order to favor a laissez-faire approach, an actor would have to believe that these challenges will remain tractable even under conditions of rapid development and intense competition—including both the competition between AI companies to create the most powerful AIs, and the competition among countries.

In the case of middle powers, there is an added challenge: if AI automates a large share of human labor, the companies providing such automation are likely to be based in superpower countries. In particular, extrapolating from current trends, they are likely to be based in the US, as this is where most frontier AI labs and the largest tech companies are based.

This means that even if superpowers manage the transition deftly and AI delivers extraordinarily positive economic outcomes, middle powers will likely find themselves in a position of diminished bargaining power, increasingly dependent on superpowers.

To summarize, we expect that for an actor to prefer a laissez-faire approach to AI development, it would have to hold the following views:

- Very high confidence that AI development will not yield geopolitically destabilizing capabilities;

- Confidence that societal, economic, and regulatory challenges arising from AI development are tractable even under conditions of intense competitive pressure and development speed;

- Confidence that all other relevant actors, especially superpowers, share optimistic assessments or that for whatever other reason, they are not prone to escalating geopolitical tensions due to AI development.

We expect this combination of beliefs to be rare in practice. Indeed, while superpowers are not currently engaged in an AI race, early signs point to a gradual shift to a more competitive posture. The US maintains export controls on AI-relevant hardware targeting China; China has plans to secure the ability to independently produce cutting-edge chips specifically so that it can stay competitive on AI.[57 Wendy Chang, Rebecca Arcesati and Antonia Hmaidi at MERICS]

Additional signs of this can be found in communications from the governments of superpowers. The US-China Economic and Security Review Commission's 2024 congressional report calls for establishing a Manhattan Project-like program dedicated to acquiring artificial general intelligence (AGI). [58 Corin Katzke, Gideon Futerman] China has advised its AI leaders to avoid travel to the US over concerns that they could be detained or pressured to divulge confidential information.[59 Reuters]

Nonetheless, some actors may perceive only modest possibilities of geopolitical disruption and so would prefer largely unrestricted competition in AI R&D. This contingent will likely perceive competition as the best way to realize AI’s full potential for scientific and economic progress.

Citations and footnotes

One can conceptualize the constituents of superpowers in a similar way to middle powers that pursue the “Vassal’s Wager” strategy. AI can enable both extreme concentration of power and “snap coups” in which existing power structures are upended by whoever can gain control of the most powerful AI systems. Given this, constituents of a winning superpower face a similar situation in which they have no recourse against a state that deserts them.

In annex 1, we provide a definition of AI that could be used for the purpose of enforcing these measures.

An international agreement on the prevention of ASI development need not prohibit all AI R&D. In ideal conditions, restrictions would only apply to AI R&D that could lead to ASI. However, it is not possible to distinguish such activities from benign ones without extensive monitoring. From a risk assessment perspective, any AI R&D activities by actors outside the agreement should be considered as potentially dangerous.

With respect to this clause, we are making a deviation from our redlines framework which generally requires deterrence measures be applied in unison by all members. This is because commitment to mutual self-defense would likely entail some form of integrated military alliance, which may conflict with current military alliances. Many countries that may otherwise be inclined to join the coalition may not be willing to join a military alliance at the time of the agreement’s creation.

The same goes for safety research. It is a common saying in the field that “alignment research is capabilities research”. Improvements in safety methods could nearly always also be used to boost capabilities to higher levels which again become unsafe even when taking the new safety methods into account.

Contact us

For any questions or feedback, please contact us at:

Alex Amadori: alex@controlai.com

Gabriel Alfour: gabriel@conjecture.dev

Andrea Miotti: andrea@controlai.com

Eva Behrens: eva@conjecture.dev